Hydrogen Production from Thermal Electricity Constraint Management

Authors

Charlotte HIGGINS, Jacob KANE, Hanna LAWRENCE - Arup, United Kingdom

Paul WAKELY - NESO, United Kingdom

Helen DUGDALE - National Gas, United Kingdom

Summary

Arup, National Energy System Operator (NESO) and National Gas Transmission (NGT) explored the potential for electrolytic hydrogen production to manage thermal constraints on the GB’s electricity transmission system. As renewable generation in the GB continues to grow, electricity flows increasingly exceed the capacity of existing infrastructure, causing the system operator to curtail renewable energy and dispatch fossil generation closer to demand, at high financial and environmental cost.

Electrolytic hydrogen production offers a way to absorb excess renewable electricity during constraint periods, reducing curtailment, enabling clean energy use and helping other sectors decarbonise. Technically, electrolysers can respond quickly to shifting grid needs. However, commercially, they are capital intensive and operate most efficiently with high utilisation. Since thermal constraints are intermittent, relying solely on constraint-driven operation undermines investment returns. Also, most hydrogen offtakers prefer steady supply, whereas constraint-led production would be variable, requiring costly storage or flexible offtake options like blending into the gas grid.

The study concludes that hydrogen facilities can support constraint management under the following conditions: (1) access to alternate electricity supply during non-constrained periods to maintain utilisation, (2) a flexible offtake and (3) a support mechanism to incentivise facilities to locate and operate to relieve grid congestion. Four contractual models were assessed to de-risk investment and fairly compensate facilities for system benefits:

- 1: simple utilisation payment per MWh during constraint periods.

- 2a: mix of seasonal availability and utilisation payments, similar to the capacity market.

- 2b: variant of 2a without seasonal pricing.

- 3: fixed availability payment for ready-response, regardless of actual use.

Each option balances risk differently between the system operator and the hydrogen producer. Contracts must be secured the ahead of hydrogen production’s FID to ensure investment viability. Ultimately, such mechanisms aim to make hydrogen production a cost-effective, grid-supportive asset while reducing system constraint costs and aiding the UK’s net-zero transition. A similar approach could be considered in other countries, with adaptations considering their specific policy, market and regulatory regimes.

Keywords

Hydrogen Production, Thermal Constraints, Electrolyser, Constraint Management, Renewable Generation, System Operator, Decarbonisation, Network Reinforcement1. Introduction

The National Electricity System Operator (NESO) manages the GB’s electricity flow 24/7, ensuring system stability within safety limits. Transmission networks have physical constraints that, if exceeded, can risk power outages. To prevent this, NESO curtails generation in constrained areas and redispatches power elsewhere, incurring thermal constraint costs—paid by consumers and with carbon implications. As renewable generation grows, especially offshore wind in the North, these constraints are expected to worsen. By 2030, constraint costs are projected between £500 million and £3 billion annually[1].

While network reinforcements by transmission operators are underway via the Accelerating Strategic Transmission Investment (ASTI) framework, long development times for network development mean limited short-term solutions exist. In response, NESO, with Arup and NGT, explored using electrolytic hydrogen production to mitigate constraints. Electrolysis, powered by renewable electricity, splits water into hydrogen and oxygen, producing green hydrogen.

This study assessed the technical, commercial, regulatory, and economic feasibility of Hydrogen Production Facilities (HPFs) using curtailed electricity. Workstreams included energy modelling to forecast future constraints costs, commercial analysis of HPFs’ viability, hydrogen offtake potential including gas grid blending, and mapping optimal facility locations. The project found HPFs could offer a flexible, lower-carbon option for managing grid constraints while supporting hydrogen market development.

2. Background review

2.1. Great Britain (GB) Context

The GB electricity transmission system moves electricity from large-scale generators, primarily in the North, to demand centres in the South. The system operates at various voltages (400kV and 275kV in England and Wales, with 132kV also used in Scotland). NESO is responsible for continuously balancing GB supply and demand. The network is divided into zones, separated by boundaries that may face capacity constraints. Constraints occur when electricity flow exceeds a boundary’s capacity. To manage this, NESO curtails generation in high-supply areas and redispatches power elsewhere, often requiring fossil fuel generation. These actions come with significant system costs, which are ultimately paid by consumers. As renewable generation has grown, particularly in Scotland and Northern England, the cost of managing thermal constraints has increased sharply, from £309 million in 2017/18 to £1.5 billion in 2022/23. On constrained days in 2022/23, the average daily cost was £4.6 million, peaking at £62.1 million on 20 July 2022.

Looking ahead, by 2030, some parts of the network will face power flows up to four times higher than current limits, with annual constraint costs forecasted between £500 million and £3 billion[4]. These rising costs highlight the urgent need for alternative solutions to manage constraints, alongside network reinforcements, to protect consumers from rising energy bills.

2.2. Low carbon hydrogen production

Electrolytic hydrogen can be used in various sectors as a low-carbon energy solution, such as in industry as feedstock or heat, in transport for heavy-duty vehicles, in aviation and shipping as a fuel or component, for heating buildings, and in power generation. It can be transported via pipelines or trailers, with pipelines offering the most cost-effective large-scale option. Up to 20% hydrogen can be blended into the gas grid short term and can be stored in geological formations to provide system flexibility.

The UK Government aims to deploy 10GW of low-carbon hydrogen by 2030[5], supported through the Hydrogen Production Business Model (HPBM), which guarantees revenue through a 15-year strike price mechanism. The first Hydrogen Allocation Round (HAR1[6,7]) funded 11 projects and 27 projects are shortlisted for due diligence as part of HAR2 (as of April 2025). These projects are encouraged to locate in areas that reduce electricity system constraints, particularly in Northern regions, and make use of excess renewable generation. The feasibility of hydrogen production near constrained boundaries depends on the facility’s ability to ramp during constraint periods and its viability, including offtake arrangements for the hydrogen produced.

2.3. Technical feasibility and commercial viability

For a HPF to respond to thermal constraints, it must quickly adjust output based on NESO signals, typically issued one hour ahead of real time. Alkaline and Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) electrolysers can respond relatively fast when in hot states. However, frequent ramping or cold starts can cause technical stress, reduce equipment lifespan, and impact efficiency and gas quality.

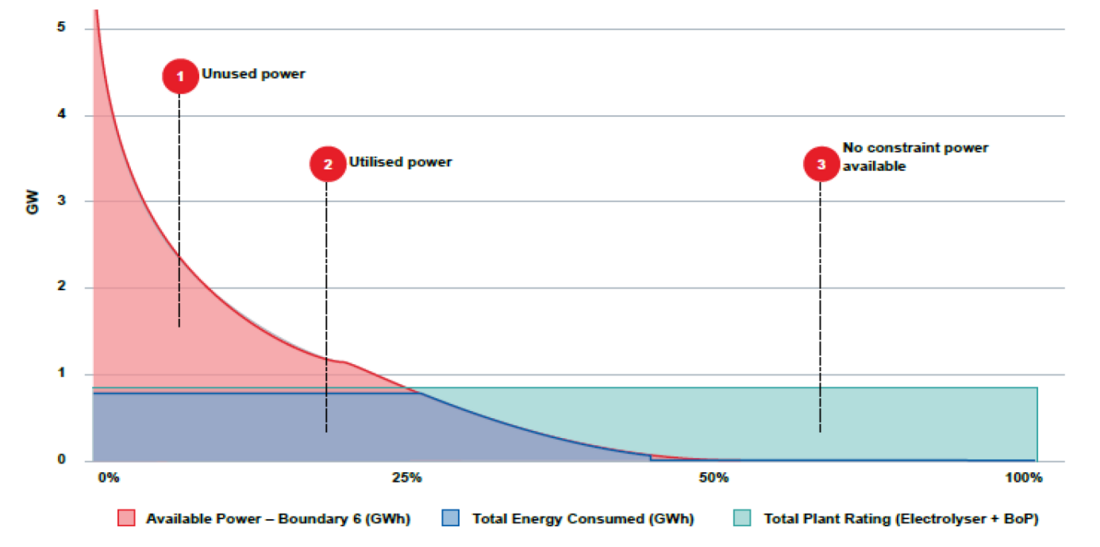

To justify the high capital costs of electrolysers, a viable business model is needed, particularly if the facility relies on intermittent operation aligned with electricity network constraints. While the Balancing Mechanism (BM) offers opportunities to access low or negative prices during high constraint periods, it is volatile and uncertain, making reliance on it commercially risky. To manage costs and maximise revenues, facilities must optimise between different power sources. However, current market structures place too much risk on investors, offering insufficient incentives for hydrogen production to locate in constrained areas or respond flexibly to network needs. Figure 1 provides an illustration of the constraints experienced (GW) within a year on any one boundary, as indicated by the curve, and the subsequent load factor, hours of the year, that the production facility would operate.

Figure 1 - Indicative load duration curve for one year (data within the graph is illustrative)

2.4. Electricity sourcing, Low Carbon Hydrogen Standard (LCHS) and offtaker flexibility

To meet the UK’s LCHS[8], hydrogen producers must prove their electricity source is low carbon. The LCHS permits the use of “electricity curtailment avoidance,” allowing facilities to use carbon intensity figures when operating during periods of thermal constraints. In regions like North Scotland[9,10,11] with surplus renewables, these figures can be close to zero, helping meet LCHS thresholds. However, such constrained electricity is intermittent, leading to fluctuating hydrogen production. Most hydrogen projects are built to serve industrial or transport offtakers, making variability a challenge. While hydrogen storage can help smooth supply, above-ground tanks have limited capacity, and underground geological storage (like salt caverns) is costly and likely viable only as part of larger networks. The most practical option for variable production is blending hydrogen into the existing gas grid, offering flexibility and scalability. Fully dedicated hydrogen networks would be ideal but are not widely available yet, thus, in the near-term, blending into the existing gas network is likely to be the most flexible offtake option.

3. Assessment methodology

Arup used PLEXOS Energy Modelling Software to assess future network constraint costs in Great Britain, focusing on thermal constraints between 2030 and 2040. The model incorporated planned network developments (from the 2022 Holistic Network Design and 2023 Electricity Ten Year Statement) and generator operating profiles. Constraint costs were analysed across boundaries B4 to B8 (i.e., areas expected to experience the highest constraints due to rising offshore wind deployment).

3.1. System costs

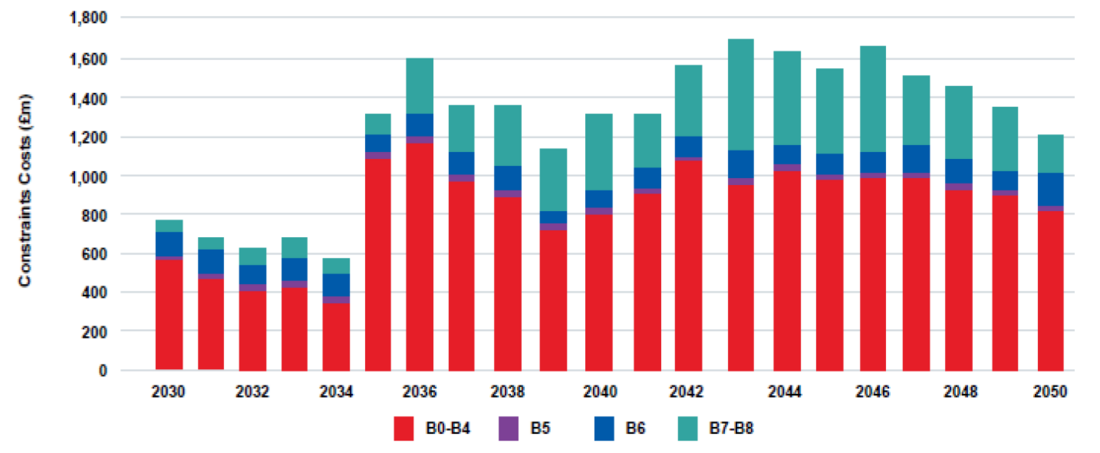

Thermal constraint costs include payments for curtailing generators behind a boundary and re-dispatching others in front to rebalance supply. The analysis found that B4 consistently showed the highest costs (Figure 3), with B6 second until 2035, after which B7 and B8 overtook. Though reinforcements under the HND and ASTI frameworks reduce costs temporarily around 2035, continued growth in renewable capacity (especially above B4) drives costs back up post-2035. In 2035–2036, the highest hours and volumes of constrained renewables were seen in B0–B4, while rising B7–B8 costs reflect growing generation in Scotland and Northern England. Instead of curtailing renewable generation, excess electricity could be redirected to produce low-carbon hydrogen. This approach could reduce constraint costs and benefit the whole energy system, ultimately easing the financial burden on consumers.

Figure 2 - Total constraint cost between 2030 and 2050 for boundaries B0 to B8

3.2. The appropriateness of using hydrogen to manage thermal constraints

Electrolysers can rapidly increase demand during periods of thermally constrained electricity, enabling low-carbon hydrogen production. However, this requires flexible offtakers who can accept variable hydrogen output. Among the options considered, blending hydrogen into the existing gas grid offers the most viable solution, providing the necessary flexibility across relevant locations and timelines. Despite technical feasibility, facilities operating only during constrained periods would have low utilisation rates, making it difficult to recover costs and leading to higher hydrogen prices. Yet, such facilities can help reduce grid constraint costs by absorbing surplus electricity. To make this business model financially viable and attract investment in strategically located hydrogen production, support mechanisms are essential.

3.3. Support mechanisms

To encourage HPFs to locate in areas with system constraints and use excess renewable electricity, the project assessed support mechanisms that align with system operator responsibilities and HPFs’ investment needs. The NESO, under its current licence, must ensure efficient and coordinated grid operation while promoting competition. Any new contract mechanism must align with these obligations. The NESO has broader responsibilities, allowing for a more strategic, integrated energy system approach.

HPFs need long-term contracts that offer revenue certainty to justify investment and reach financial close. Given the ongoing cost gap between hydrogen and fossil fuels, such projects are also expected to require support under the UK Government’s HPBM[12]. To ensure good value in managing constraints, historical and future constraint cost data were reviewed. Thermal constraints have historically peaked in winter but can be impactful year-round. Future projections show areas like B4 could continue to see high constraint costs beyond 2030, highlighting the potential value of strategically located HPFs to help manage these costs.

3.4. The value of a support mechanism

The proposed support mechanism would incentivise HPFs to increase electricity demand during periods of grid constraint, helping to absorb excess renewable generation. To ensure value for money, a ceiling price would cap payments so that costs remain lower than the NESO’s alternative of paying generators to curtail output via the balancing mechanism. This ensures the mechanism delivers greater system-wide benefits than the status quo. Participation would require HPFs to meet technical prequalification criteria, and contracts would be allocated competitively based on delivering the best whole-system value for consumers. The mechanism is designed to align with new planning processes, particularly the Centralised Strategic Network Plan (CSNP), which evaluates broader system solutions. Both new and existing facilities could access the mechanism, provided they are suitably located to support thermal constraint management.

4. Findings

4.1 The contract options

This project outlines four potential contract mechanisms that could provide signals for HPFs to respond during periods of electricity system constraints. Each mechanism balances risk and reward between the hydrogen producers and consumers, with penalties for non-availability and a focus on providing value during peak periods:

- 1. Utilisation Payment: HPFs are paid a utilisation fee (£/MWh) for responding to constraints. Contracts range from 1 to 10 years and are procured up to 4 years ahead of need. Providers must confirm availability in advance and meet a minimum availability level to receive full payment. Penalties apply if they use

the BM instead. - 2a. Seasonally Varying Utilisation and Availability Payments: This option adds an availability payment (£/MW) to the utilisation payment. The payment varies between autumn/winter and spring/summer, reflecting higher constraint impacts in colder months. The contract duration is typically 10 years for new facilities, aligning with network upgrades. Providers must meet minimum availability and can face penalties.

- 2b. Year-round Utilisation and Availability Payments: Similar to Option 2a, but the payments remain fixed throughout the year. The contract duration and procurement process are the same as 2a. Minimum availability and penalty clauses apply.

- 3. Fixed Payment: Providers receive a fixed payment for the level of demand response they commit to, based on avoided premium costs. This contract is typically for 1 year and includes the same dispatch windows and penalties for non-availability.

The contract for HPFs during thermal constraints aims to optimise utilisation and business models during periods of no constraints, such as through PPAs or BM. The contract allocation mechanism may include an auction or allocation window approach, each suited for different market conditions. The auction approach depends on market liquidity, with less competition potentially driving up prices. Alternatively, allocation windows could offer a more strategic approach, involving a tender process based on system needs, which may align with the CSNP[13]. This method would evaluate bids on technical, deliverability, and commercial criteria, ensuring optimal outcomes.

Risk allocation is a key factor, with different options balancing price and volume risk between the ESO and HPFs. Option 1 places volume risk on HPFs, while Options 2a and 2b offer a more balanced approach, providing some revenue certainty to HPFs through availability payments. Option 3 transfers both volume and price risk to the ESO. The overall goal is to secure optimal consumer benefits while considering the broader hydrogen market and decarbonisation objectives, ultimately reducing costs for consumers and taxpayers.

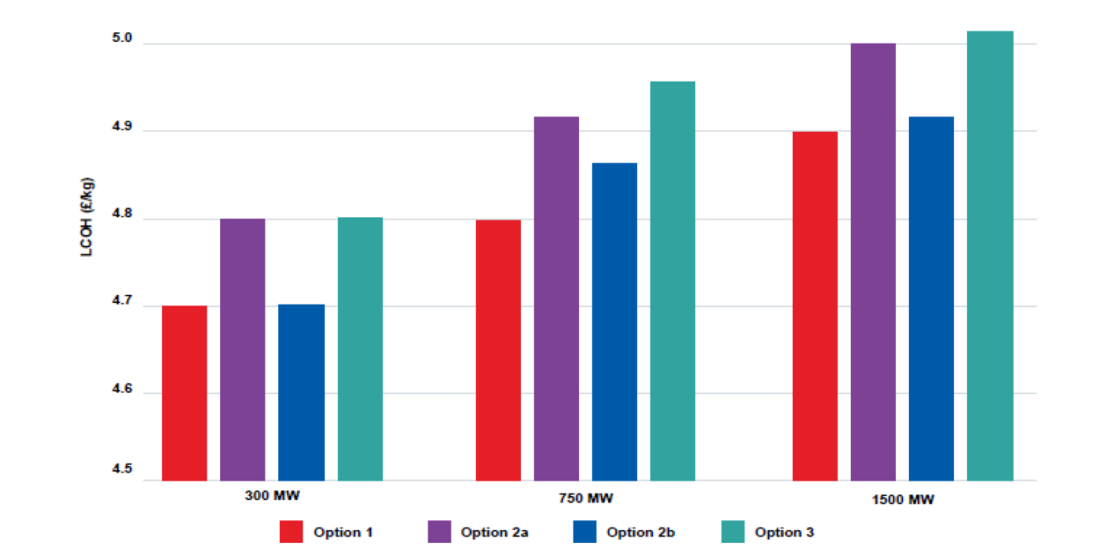

To assess viability, the Levelised Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH) was modelled for hydrogen production using constrained electricity, with results compared to production using renewables via a PPA. Modelling was conducted for 300MW, 750MW, and 1500MW facilities producing hydrogen for grid blending. Results showed that all contract options reduced LCOH compared to using PPA electricity, as shown on Figure 2. In 2030, the LCOH ranged between £4.7–£5.0/kg, with potential to fall to £3.6–£3.9/kg by 2036 under higher constraint conditions. These figures compare favourably to wider UK estimates of £3.90–£9.50/kg[14]. The LCOH is highly sensitive to technical factors (e.g., electrolyser CAPEX, storage requirements), while contract parameters had less impact. Utilisation rate is a key driver: lower utilisation increases costs due to underused assets. Contracts help offset these inefficiencies, providing revenue certainty to producers responding to system constraints. While differences between contract types were minor, they mainly affect the distribution of risk between the ESO and hydrogen producers.

Figure 3 - LCOH range for contract options using 2030 modelled constraints profile

4.2. Results

The analysis found that using otherwise-curtailed renewable electricity for green hydrogen production can reduce electricity system costs. Typically, when the NESO calls on assets to resolve thermal constraints, these generators charge a price premium due to the short-notice nature of the BM. The main benefit of hydrogen facilities lies in avoiding these premiums. By redirecting excess renewable power to hydrogen production instead, this demand can be scheduled in advance and met through the open market (e.g., day-ahead market), where prices are generally lower and more competitive. Introducing hydrogen demand in constrained areas increases known electricity demand, which shifts both supply and demand away from the BM into regular markets. This helps avoid the inflated prices generators typically charge in the BM and encourages more cost-effective generation offers.

Stakeholders’ feedback on specific contract options revealed that Option 1 was felt risky for developers and would be unlikely to provide sufficient certainty. Option 3 was attractive due to payment certainty, but the short duration was a barrier. Option 2 was seen as a better balance of risk, but developers expressed concerns about penalty payments for non-availability. Wider issues raised included long electricity connection timelines[15], which could hinder the potential benefits of thermal constraints management, and concerns about indexation mechanisms for hydrogen producers needing more flexibility to manage electricity price volatility.

5. Conclusions

Planned network reinforcements will eventually address thermal constraints, but the process will take time. HPFs offer an alternative method to manage these constraints by utilising otherwise constrained electricity to produce low-carbon hydrogen.

The findings confirm that HPFs can support constraint management. Electrolysers can adjust their output to align with periods of network stress, and hydrogen production can be integrated with flexible offtakers, like the gas network, which could blend hydrogen into the existing infrastructure. However, current market and regulatory conditions do not incentivise locating hydrogen production in constrained areas or using electricity during these periods. Additional support, possibly via a contract with the NESO, is needed for HPFs to be commercially viable and effectively manage thermal constraints. While HPFs could contribute to managing thermal constraints, they are not a complete solution and will be part of a broader demand response strategy. Only some HPFs may be suited, and their involvement will be time-bound, as network reinforcements are expected to reduce the need within 15-20 years.

Overall, the paper explored several contract options to incentivise HPFs, each with varying levels of risk for the NESO, consumers, and producers. These contracts must be finalised soon to align with development timelines, ensuring HPFs can provide the intended benefits. A similar approach could be considered in other countries, with adaptations considering their specific policy, market and regulatory regimes.

References

- Electricity Network Operator (2022), Markets Roadmap 2022, National Grid ESO

- National Grid ESO (n.d.), The Pathway to Holistic Network Design

- UK Government, Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2023), Powering Up Britain

- National Grid ESO (n.d.), Electricity Ten Year Statement (ETYS)

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2021), UK Hydrogen Strategy

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2023), HAR1: Successful Projects

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2024), HAR2

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2023), UK Low Carbon Hydrogen Standard: Emissions Reporting and Sustainability Criteria. See Section B.22

- National Grid ESO (n.d.), Electricity Distribution Network Areas

- National Grid ESO (n.d.), Regional Carbon Intensity Forecast

- Elexon (n.d.), Balancing Mechanism Reporting Service (BMRS)

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2022), HPBM

- Ofgem (2023), Decision on the Framework for the Future System Operator’s Centralised Strategic Network Plan

- BloombergNEF (2023), High UK Green Hydrogen prices reflect power grid costs

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero and Ofgem (2023), Electricity Connections Action Plan