Impact of MVDC Cables on the Energy Transition

Uwe SCHICHLER, Patrik RATHEISER - Graz University of Technology, Institute of High Voltage Engineering and System Performance, Graz, Austria

Andrew LAPTHORN, Nalindi HERATH - University of Canterbury, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Christchurch, New Zealand

Summary

Electricity plays an important role in enabling the energy transition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050. Having DC subsystems at all voltage levels will enable more efficient transmission of electricity, reduce the number of converters and hence losses, and result in a more reliable system.

MVDC cables will be a key technology for the future. The refurbishing of existing MVAC cables resp. the application of new MVAC XLPE cables for DC operation is very promising. The basic idea is to allow a mean electric field of 10 kV/mm for MVDC cables, which today’s MVAC cables can fulfil. In this context, it is a clear benefit that today’s MVAC cable systems are accompanied by a stable supply chain and well-standardised quality assurance methods.

Intensive research was done to understand the DC phenomena of extruded MVAC cables. The investigations described here deal with the increase in transmission capacity, the conductivity and space charge accumulation thresholds of MVAC XLPE, electrical treeing under DC, breakdown strength under TOV stress and optimized type test and PQ test procedures.

The aforementioned work has shown that reliable MVDC cable systems are available against this background.

Keywords

Breakdown, Cables, Conductivity, DC, Energy Transition, MVDC, Testing, Treeing1. Introduction

There is great concern around the world about climate change caused by human activity (anthropogenic). International organisations (e.g. IEA) and governments are setting strategies to reduce the carbon footprint and deadlines for achieving net-zero emissions. Electricity is central to many areas of modern society and plays an important role in enabling the energy transition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050. However, to achieve this, electricity generation must be renewable and not contribute to greenhouse gases. First, the electricity system must be decarbonised. This has driven the rapid expansion of electricity generation from renewable energy sources, both in the supply sector and among consumers. This does add complexity to the design and management of the electricity grid. The intermittent nature of solar and wind energy requires a range of backup power generation options to be available. The rapid electrification of many end-users, from transport to industry, is driving an increase in demand for electricity, and it is important that this additional demand is met by renewable sources rather than fossil fuels (gas and coal). The electricity grid is a key component in enabling this energy transition as it connects generation to loads and must be able to cope with the increasing use of decentralised energy resources and the intermittent nature of some. Security of electricity supply and affordability are high priorities for society. Security of electricity supply requires resilient infrastructure and a reliable electricity system, which are central to the energy transition. Significant efforts are being made worldwide to build new transmission capacity for rapidly growing renewable generation. However, maintenance is also an important factor in regard to reducing the risks of existing assets [1].

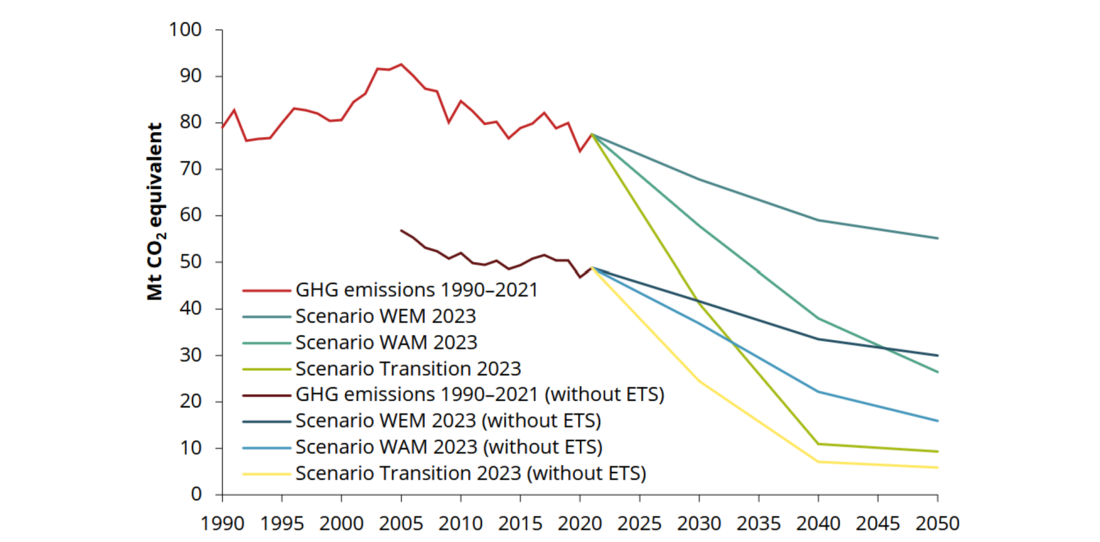

For Austria, the current regulations stipulate a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (outside the emissions trading system, ETS) of 48% by 2030 as compared to 2005 (EU-wide target: - 40%). In relation to 2022, this means that a reduction of emissions from non-ETS sectors by 36% will be required (Fig. 1). The National Energy and Climate Plan, with its detailed measures, define the framework for the needed transformation and will be adapted to meet the new European Green Deal targets to achieve national climate neutrality by 2040 [2].

Figure 1 – Austrian Trend in Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Scenarios to 2050

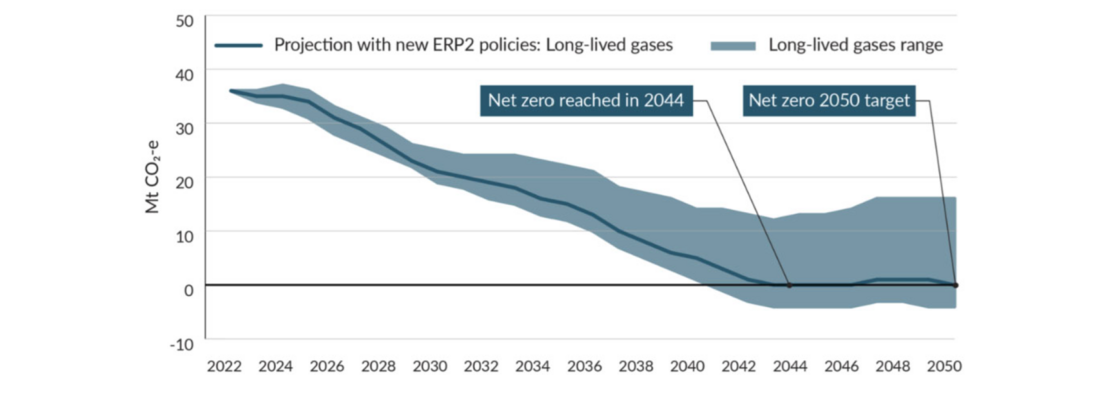

New Zealand has long-term climate targets: all greenhouse gases, except methane emissions from waste and agriculture biological processes, are to reach net-zero by 2050 (Fig. 2). The government released the second emissions reduction plan (ERP2) in December 2024. The actions and initiatives of this plan will put NZL on track to meet the 2050 net-zero target. The required CO2 reduction also includes the energy sector, where, among other topics, a smarter electricity system is to be enabled [3].

Figure 2 – Net Emissions in NZL, excluding biogenic methane, and sensitivity range with ERP2 measures

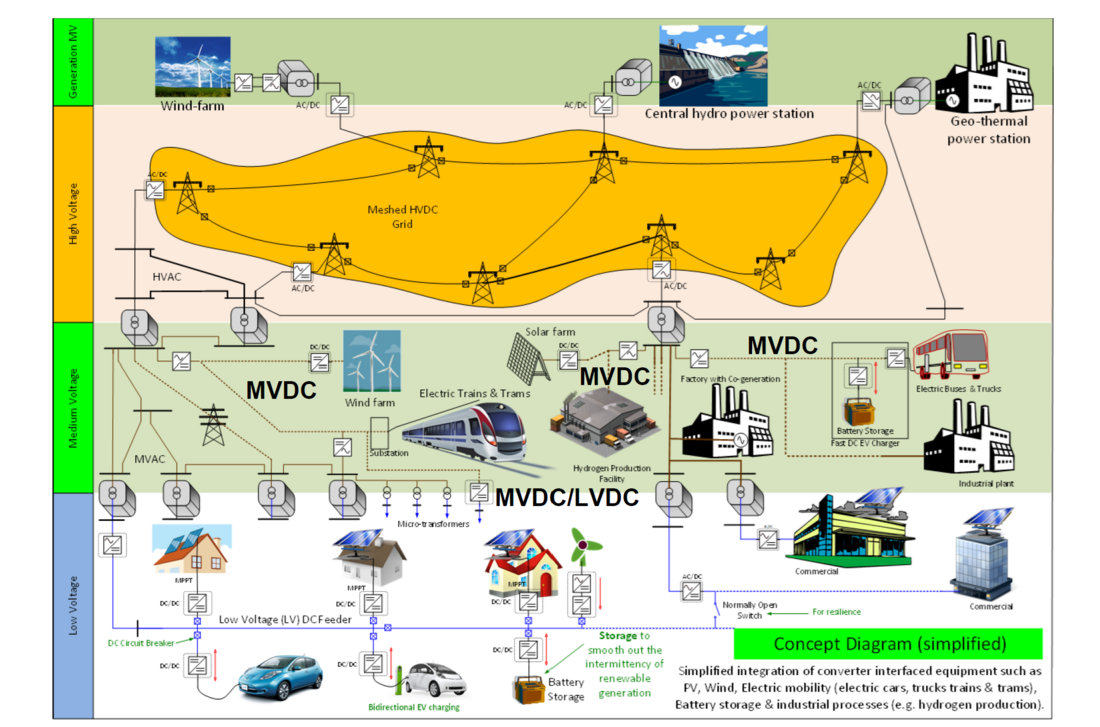

Many of the new technologies that are key to the energy transition are DC based and require interfacing with the existing AC power system. Having DC subsystems at all voltage levels will enable more efficient transmission of electricity, reduce the number of AC/DC and DC/AC converters and hence losses, and result in a more reliable system. Therefore, the planned architecture of the future electrical network is a hybrid AC/DC power system (Fig. 3). DC systems, including HVDC/MVDC cables, will be key technologies for the future [1, 4 - 7].

Figure 3 - Future Hybrid AC/DC Electrical Network

2. DC-based Energy Transition Projects in Austria and New Zealand

2.1. Research Activities in Austria

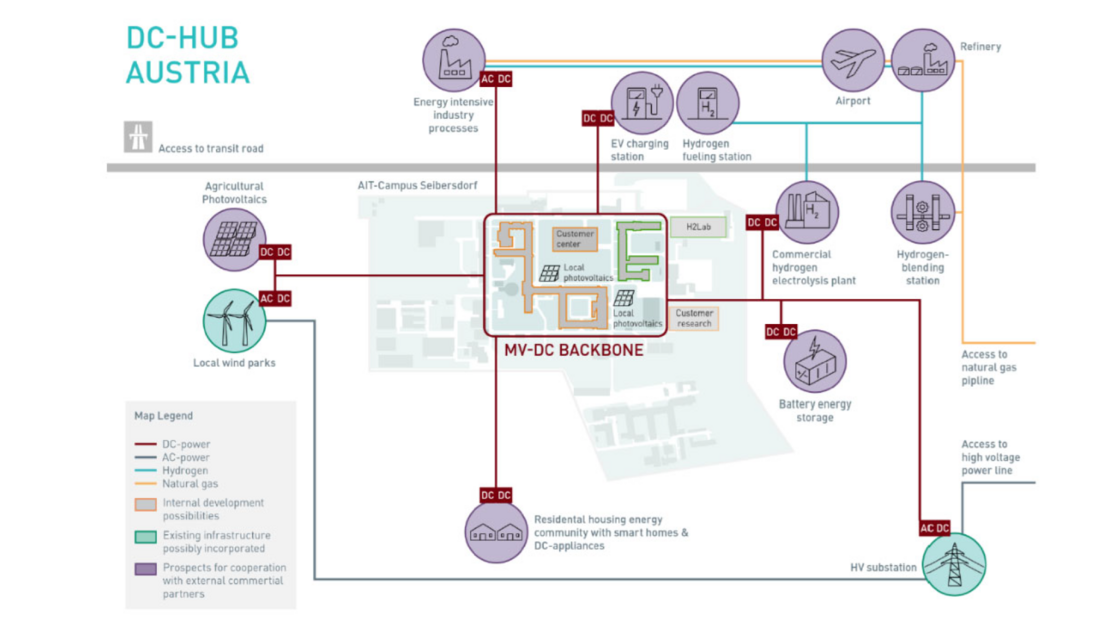

Already in 2017, the Graz University of Technology (TU Graz) had started research into the disruptive field of MVDC technology, mainly focussing on MVDC cable systems [6, 8]. An intensive consultation was held with distribution grid operators from 2019 - 2021 to identify future use cases for MVDC. Additionally, in 2020, the Austrian Electrotechnical Association started an initiative to support the Austrian DC activities of research institutes, utilities and industry in the field of LV/MVDC. In 2025, TU Graz and the Austrian Institute of Technology are investigating the technical and economic feasibility of a research and demonstration platform for an MVDC distribution system, as part of the publicly funded project ‘DC Hub Austria’ [9]. This platform is intended to promote technology development in the field of MVDC systems through research infrastructure. It is intended to act as a catalyst for new developments and provide infrastructure that small and medium-sized industrial companies are unable to build (Fig. 4). The feasibility, advantages and limits of MVDC systems should be demonstrated in practice. It would currently be the first MVDC system in Austria to be connected to wind, photovoltaic, electrolysis and fast-charging systems with significant electrical power. This is of great importance, as Austria will have to invest around 44 billion Euros in the distribution grid by 2040 [10].

Figure 4 – Schematic of R&D project “DC-Hub Austria”

2.2. Future Architecture of the Network (FAN) Programme in New Zealand

The FAN programme was awarded in 2020 and aims to develop knowledge and understanding of the extent to which DC technology should penetrate the existing AC network, and also the associated challenges and solutions [1]. A transition pathway is to be determined that makes the best use of existing infrastructure. The programme is strategic as the time horizon is 2050 and beyond. Besides the technical KPI, there are also KPI around training researchers in this emerging technology as well as creating benefit to Māori and under-represented groups.

Training can involve undertaking PhD studies and research, it also involves bringing expertise to New Zealand or sending researchers overseas for a period. Input via overseas co-supervisors also contributes to the outcome of the projects. The initial FAN team consisted of five New Zealand universities (University of Canterbury, University of Auckland, Auckland University of Technology, University of Waikato and Victoria University of Wellington) and one UK university (University of Cambridge). The FAN programme is split into five workstreams:

- Workstream 1: Network Architecture

- Workstream 2: Topology

- Workstream 3: Converter topology, operation and enabling technologies

- Workstream 4: Transition Path (includes research on MVDC cables)

- Workstream 5: Vision Mātauranga

Rather than designing fixes that allow new technologies such as MVDC to operate in the present AC system, this project looks at what would be the best system for the future in order to meet the many objectives, such as allowing easy integration of new technologies, improve efficiency and thereby developing a low-carbon system, which is good for our planet. At the same time it needs to be cost-effective, reliable and resilient, particularly as more extreme weather events seem to be more common. Continuing to apply fixes to allow the new technologies to operate in the present AC system will result in a patch-up network that does not meet these objectives.

3. MVDC Technologies and Applications

3.1. Equipment

Applications of MVDC technologies for shipboard systems, railways, offshore wind farm connections, data centers, and distribution grids are under discussion or already available in many countries like the UK, France, China and Korea [11 - 15]. The typical DC voltage levels are 3 kV resp. ±1.5 to ±50 kV, and the related powers range between approx. 3 to 1,000 MW [16]. Each MVDC application has specific equipment requirements and makes use of AC/DC and DC/DC converters, solid state transformers, DC circuit-breakers, DC overhead lines, DC cables, and DC protection systems. Some of the aforementioned equipment is already on the market or under development.

3.2. Projects (Examples)

The Angle DC project in the UK converted two existing 33 kV AC lines between the island of Anglesey and the Welsh mainland into ±27 kV DC operation, increasing the power capacity of the lines by 23% to 30.5 MVA [11, 14]. The Jiangdong ±10 kV MVDC distribution network in Hangzhou (China) is a demonstration project, aiming to promote reliability, interaction, and cost-effectiveness. The project was commissioned in 2018 [14]. In Korea, a ±35 kV MVDC station was built in 2023 (Naju project, 30 MW). It made use of containers to enable the system to be rapidly built without the need for any separate building [15]. Built as a demonstration, a 900 m long linear photovoltaic power plant (1 MWpeak) in France will be based on a ±5 kV MVDC collection network (Ophelia project) that consists of three DC/DC converter stations and a single DC/AC converter [17]. The commissioning is scheduled for 2025.

4. MVDC Cables

4.1. Basic Phenomena in DC Cables

The electric field distribution at DC voltage is determined by the conductivity, which has a strong dependency on temperature and electric field strength. This leads to several technical effects that do not occur under AC stress [18, 19].

Thermal runaway: The temperature-dependent conductivity of the insulation material can lead to low insulation resistance at high temperatures. This results in an increased direct current through the cable insulation and related further heating of the dielectric. This continuously progressive heating leads to a thermal breakdown. In the past, the described effect limited the maximum conductor temperature for XLPE insulated DC cables to 70 °C and was excluded for modern extruded DC cables by appropriately selected and modified insulation materials.

Field inversion: The electric field distribution in a DC cable depends on the temperature and electric field strength-dependent conductivity of the insulation material used. A temperature gradient ΔT in the cable insulation - caused by the current heat losses of the cable conductor - leads to a reduction in the electric field strength on the inner conductor and to an increase in the field strength on the outer conductor.

Accumulation of space charges: Polymer insulating materials such as XLPE are able to store free charge carriers. The resulting temperature-, field strength-, and time-dependent accumulation of space charges influence the electric field distribution in the cable insulation and can lead to failures, especially after a polarity reversal. The measurement of space charges can be carried out experimentally using different methods (PEA, TSM). With suitable measures and modifications of the insulating material, it is possible to minimize the space charge formation.

4.2. History of Extruded DC Cables

In the early days, DC cables were used mainly in the form of paper-insulated submarine cables (OF, MI, PPLP) for transporting energy over long distances. Since the end of the 1990s, extruded DC cables with PE/XLPE insulation have also been in use, which are currently available up to ±525 kV [18]. DC cables for ±640 kV have passed the required tests [20]. The success story of extruded DC cables can be traced back to the following HVDC projects.

- The first HVDC project with XLPE insulated DC cables was commissioned in 1999 with a transmission capacity of 50 MW and a length of 72 km (Gotland Link project). It is a ±80 kV DC cable system with an insulation thickness of 5.5 mm.

- In 2002, the Murraylink project was the first commercial ±150 kV XLPE DC cable system including almost 400 joints, which enables a reversible power flow of more than 200 MW over a 177 km distance. The insulation thickness is 12 mm.

- Another important milestone was the commissioning of the 400 MW HVDC project Trans Bay in San Francisco in 2010. The ±200 kV DC cables used for the first time world-wide have a copper conductor with a conductor cross-section of 1,100 mm².

- An XLPE DC cable system with a rated voltage of ±320 kV and a transmission capacity of 800 MW was used for the first time in the HVDC project DolWin 1. The transmission line has a length of 165 km and was commissioned in 2014.

- The German onshore EHV grid will be enforced by several ±525 kV DC cable systems (e. g. Südlink project, transmission capacity: 2 GW). The cables will have a conductor crosssection of 2,500 mm² or more and an insulation thickness of at least 26 mm. The insulation material will be XLPE or HPTE. Work has already begun on laying the cable systems.

Testing of extruded DC cables was first described in 2003 for rated voltages up to 250 kV and updated in 2012 for rated voltages up to 500 kV by CIGRE TB 496. IEC 62895 was published in 2017. It was based on CIGRE TB 496 and limited to land cables up to 320 kV. In 2021, the CIGRE TB 852 replaced TB 496 and deals with testing of DC cable systems up to 800 kV [21]. New aspects include thermal stability testing and tests with different temporary overvoltages.

4.3. Research Activities

The demand for MVDC cables can be seen through the increasing number of scientific publications worldwide. The refurbishing of existing MVAC cables resp. the application of new MVAC XLPE cables for DC operation is very promising [6, 14, 22, 23]. The basic idea of TU Graz is to allow a mean electric field of about 10 kV/mm for MVDC cables, which today’s MVAC cables can fulfil. In this context, it is a clear benefit that today’s MVAC cable technology is accompanied by a stable supply chain and well-standardised quality assurance methods.

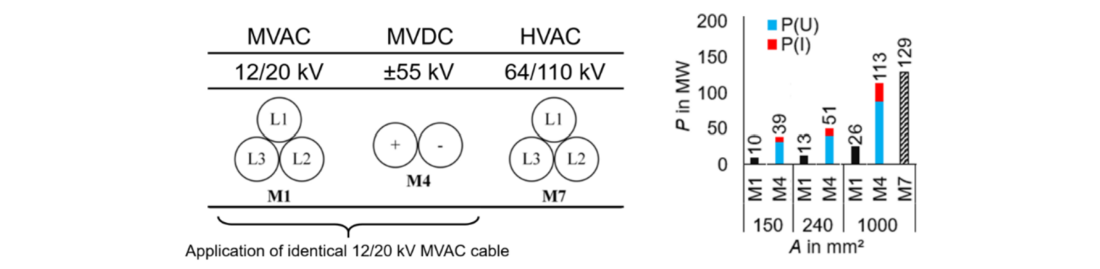

Transmission capacity: The conversion of MVAC cable systems to DC operation leads to an increase in transmission capacity [11, 24]. The reason for this is a permissible increase in the operating voltage and an increased current due to the missing skin and proximity effect. A DC voltage equal to the peak value of the single-phase AC voltage results in a negligible improvement. However, using 12/20 kV MVAC cables (5.5 mm insulation thickness) for a ±55 kV MVDC cable system (mean field stress of 10 kV/mm) results in a significant increase in transmission capacity by a factor of about 4 (Fig. 5). In case of a large conductor cross-section (e.g. 1,000 mm²), such an MVDC cable system can almost replace a 64/110 kV HVAC cable system.

Figure 5 – Transmission systems, cable arrangements, and capacities for different conductor cross-sections

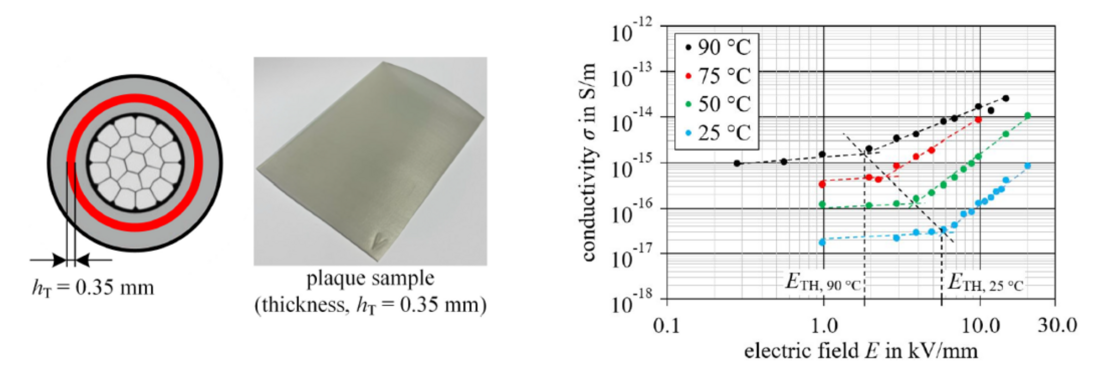

Conductivity: The DC conductivity of polymers depends on the applied electric stress, temperature, and time. It shows a strong nonlinear behaviour with respect to these parameters and strongly influences the electric field in the insulation material. The space-charge-limited current (SCLC) theory shows how the electric conductivity changes depending on the electric field. The accumulation of space charges results in a threshold, after which the electric conductivity rises faster than in the ohmic region (trap-limited SCLC). Plaque samples were taken from standard 12/20 kV MVAC XLPE cables to investigate the conductivity of the insulation material and to identify the temperature-dependent electric threshold for space charge accumulation (Fig. 6). The apparent conductivity was calculated from leakage current measurements (pA range) within an applied electric field strength of 0.3 to 20 kV/mm and for temperatures ranging from 25 to 90 °C [25]. It can be seen from Fig. 6 that the electric threshold at 25 °C occurs at about 6 kV/mm, while at 90 °C the electric threshold was observed at about 2 kV/mm. The obtained conductivity ranges from about 10-17 to 10-14 S/m. It should be noted that other MVAC XLPE materials may have different values for conductivity and space charge accumulation thresholds.

Figure 6 – Plaque samples taken from 12/20 MVAC XLPE cable and apparent conductivity

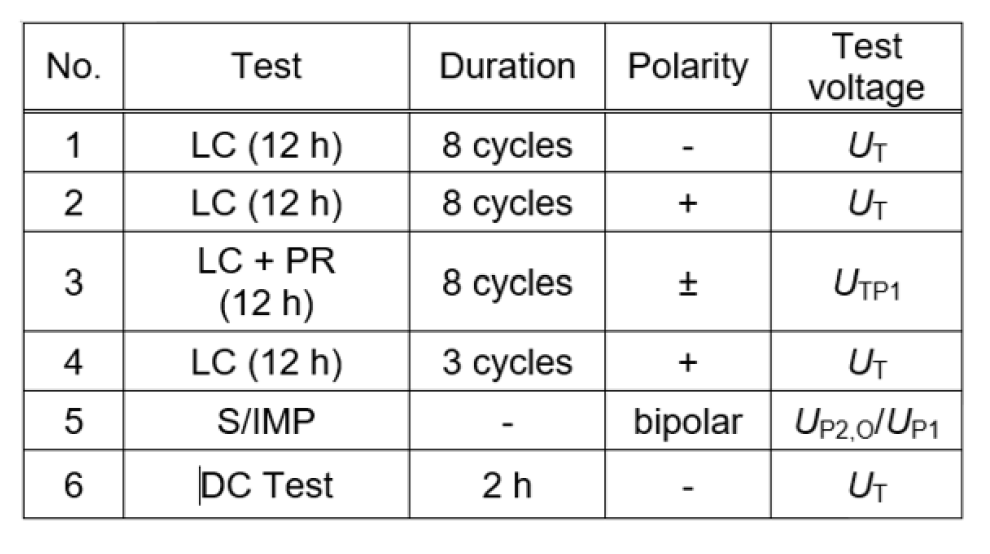

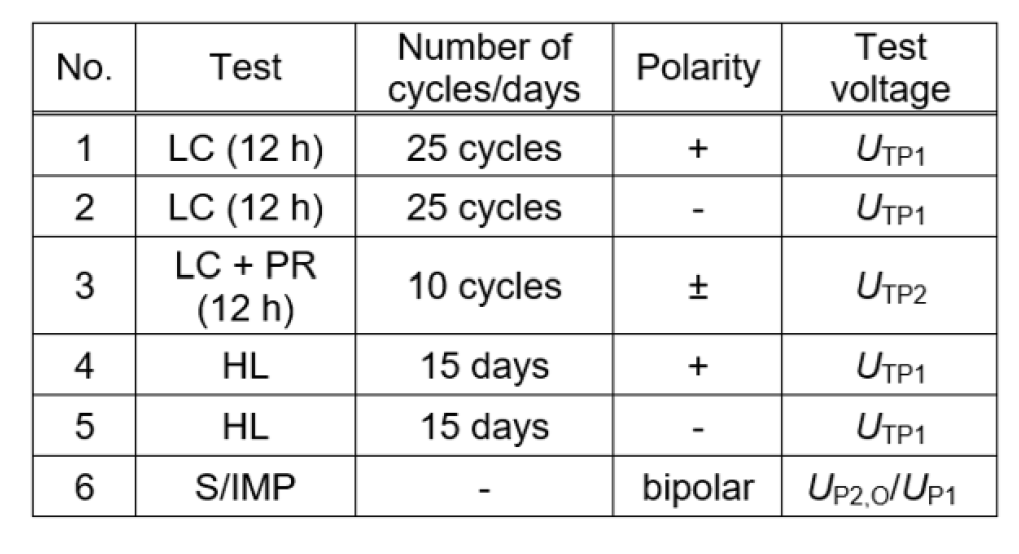

Type test and PQ test: CIGRE TB 852 describes the type test and PQ test for extruded HVDC cables. However, for MVDC cables the aforementioned tests can be significantly optimized in terms of time due to a lower thermal time constant, shorter dielectric time constant, and a more realistic life exponent for the inverse power law model of N = 15 (Table 1, Table 2). With regard to the worst case, the optimized LCC test procedures were applied to various 12/20 kV MVAC XLPE cable systems including standard accessories, and passed without objection with respect to a ±55 kV MVDC cable system operating at a mean electric stress of 10 kV/mm and at temperatures of 90 °C [22]. A more detailed discussion of the test procedures and a description of optimized VSC test procedures can be found in [26, 27]. There was never a breakdown during testing although the maximum electric stress with 14.5 kV/mm (PQ test) resp. 18.5 kV/mm (type test) was far above the identified electric thresholds for space charge accumulation.

Table 1 – Optimized LCC type test for MVDC cables

Table 2 – Optimized LCC PQ test for MVDC cables

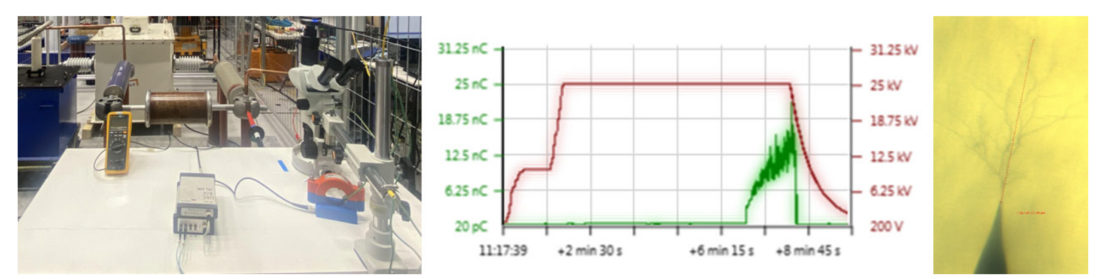

Electrical treeing: Electrical treeing is a pre-breakdown phenomenon and is considered as the main cause of breakdown in XLPE cables. It originates from distorted local electrical fields due to impurities, voids, and defects within the cable dielectric [28, 29]. Extensive experiments with a pin-plane electrode arrangement (Ogura needle with 3 μm tip radius, gap: 2 - 4 mm) were performed under DC voltage and DC/AC composite voltage (50 Hz AC to simulate harmonics) at room temperature. The test samples were taken from a 19/33 kV MVAC XLPE cable with a 6.5 mm insulation thickness. A microscope with a CMOS camera was used to visualise and record the tree growth, and all measurements were done with a simultaneous partial discharge measurement (Fig. 7). The results could be summarized as follows:

- No electrical treeing was observed under constant DC voltage of up to 33 kV for 20 min.

- With a composite voltage of 25 kV DC and 5 kV AC, a steady increase in PD and no tree growth were observed.

- Growth of an electrical tree was observed when a composite voltage of 24 kV DC and 6 kV AC resp. 25 kV DC and 10 kV AC was applied to the samples (Fig. 7). A tree length of about 345 μm resp. 800 μm was detected.

- Introduction of AC voltage on DC voltage can decrease the insulation resistance towards degradation. Further testing with realistic harmonics and consideration of space charge accumulation in front of the needle should be performed.

Figure 7 – Test setup, PD activity, and electrical tree (797.5 μm) at composite DC/AC voltage of 25/10 kV

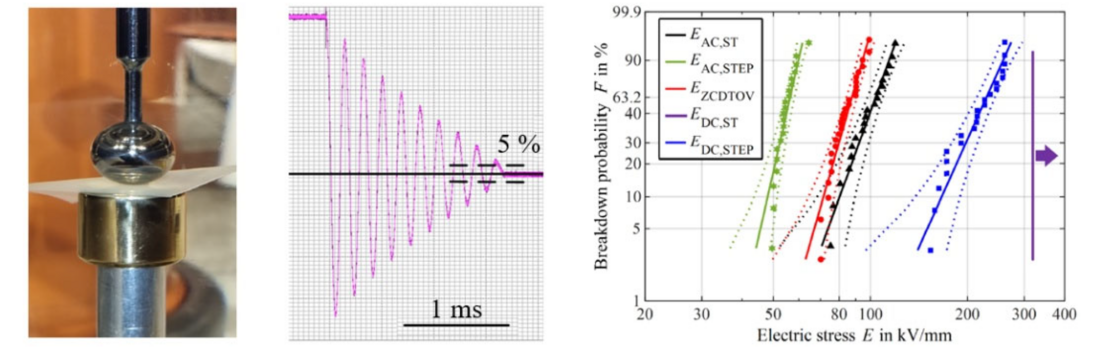

Breakdown strength under TOV: DC cable systems will be exposed to a zero crossing damped temporary overvoltage (ZCDTOV) in case of failure [21]. The dielectric strength of XLPE stressed with ZCDTOV is therefore of interest in comparison to AC and DC breakdown voltage. Plaque samples with a thickness of 400 μm were taken from 12/20 kV MVAC cables and tested at room temperature with a sphere-plane electrode arrangement. The performed breakdown tests for AC,ST (AC short-time test), AC,STEP (AC 20 s step-by-step test), DC,ST (DC short-time test), and DC,STEP (DC 20 s step-by-step test) were carried out in accordance with IEC test procedures. A ZCDTOV frequency of 5.5 kHz was selected for the tests. Fig. 8 shows the results of the breakdown tests for AC, DC, and ZCDTOV. It can be seen that the dielectric strength is highest for DC,ST (>320 kV/mm). The dielectric strength for DC,STEP (229 kV/mm) is about four times higher than for AC,STEP (56 kV/mm). The dielectric strength under ZCDTOV is 87 kV/mm, which falls between the results of the AC and DC step tests. Breakdown test results under slow front TOV stress (SFTOV) are also available [30].

Figure 8 – Electrode arrangement, ZCDTOV waveform, and breakdown field strength

4.4. Activities at CIGRE

So far, no IEC standard exists for MVDC cables. For this reason, the CIGRE SC B1 founded the CIGRE TF B1.82 back in 2021. The TF clarified the need for MVDC cables, summarized the current technical status and prepared the terms of reference for the subsequent WG B1.82, which started working on the requirements for MVDC cable systems in 2022. A Technical Brochure is expected in 2026, and the results will be used for the IEC's standardisation work.

5. Conclusions

Electricity plays an important role in enabling the energy transition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050. Having DC subsystems at all voltage levels will enable more efficient transmission of electricity, reduce the number of converters and hence losses, and result in a more reliable system.

MVDC cables will be a key technology for the future. The application of new MVAC XLPE cables for DC operation is very promising. The basic idea is to allow a mean electric field of 10 kV/mm for MVDC cables, which today’s MVAC cables can fulfil. In this context, it is a clear benefit that today’s MVAC cable systems are accompanied by a stable supply chain and well-standardised quality assurance methods. Extensive research work has shown that reliable MVDC cable systems are available against this background.

References

- Watson, Mukhedkar, Nair, Lie, Lapthorn, Merrit, Rayudu, Hart: The Electrical Power System of the Future: DC Systems’ Role in the Future. EEA Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2024

- Austrian Umweltbundesamt: Klimaschutzbericht 2024. Report 0913, 2024 (in German)

- NZL Ministry for the Environment: New Zealand’s Second Emissions Reduction Plan 2026 - 30. Internet, 2024

- Hay, McFadzean, Cleary: Evaluation of the Potential Market for MVDC Technology and its Future Development. CIGRE Session, Paris, France, Report B4-302, 2016

- Bathurst, Hwang, Tejwani: MVDC - The New Technology for Distribution Networks. Conference on AC and DC Power Transmission, Birmingham, United Kingdom, 2015

- Rainer, Renner, Buchner, Schichler: Medium Voltage DC Transmission: A New Approach for the Power System. CIGRE SEERC Conference, Vienna, Austria, Report 1140, 2021

- Mazzanti: High Voltage Direct Current Transmission Cables to help Decarbonisation in Europe: Recent Achievements and Issues. High Volt, Vol. 7, No. 4, 2022

- Schichler, Buchner: Application of extruded AC Cables for Medium-Voltage Direct Current Transmission (MVDC). Conference on High Voltage Engineering, Berlin, Germany, 2018 (in German)

- Schichler, Ratheiser, Kupzog, Mayr: DC-Hub Austria - Exploratory study for a DC technology incubator in Austria. IEWT, Vienna, Austria, 2025 (in German)

- Austrian Institute of Technology: Update of the grid calculations of the study ‘Economic value of electricity distribution grids on the way to climate neutrality in Austria’. 2024 (in German)

- Yu, Smith, Urizarbarrena, MacLeod, Bryans, Moon: Initial Designs for Angle-DC Project: Challenges Converting Existing AC Cable and Overhead Line to DC Operation. CIRED, Glasgow, United Kingdom, Report 0974, 2017

- Coffey, Timmers, Li, Wu, Egea-Alvarez: Review of MVDC Applications, Technologies and Future Prospects. Energies, No. 14, Vol. 21, 2021

- CIGRE WG C6.31: Medium Voltage Direct Current (MVDC) Grid Feasibility Study. CIGRE TB 793, 2020

- CIGRE JWG C6/B4.37: Medium Voltage DC Distribution Systems. CIGRE TB 875, 2022

- Lee: The First MVDC Station Project in Korea. ELECTRA, No. 326, 2023

- IEC TS 63354: Guideline for the Planning and Design of DC or Hybrid Microgrids, Committee Draft, 2025

- Dworakowski, Marache, Lamard, Ramondou: Linear PV Power Plant based on MVDC Collection Network. CIGRE Session, Paris, France, Ref. B4-10311-2024, 2024

- Mazzanti, Marzinotto: Extruded Cables for High-Voltage Direct-Current Transmission. IEEE Press, Wiley, USA, 2013

- Chen, Hao, Xu, Vaughan, Cao, Wang: Review of High Voltage Direct Current Cables. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2015

- Jeroense, Bergelin, Quist, Abbasi, Rapp, Wang: Fully qualified 640 kV underground extruded DC cable system. CIGRE Session, Paris, France, Ref. B1-309_2018, 2018

- CIGRE WG B1.62: Recommendations for testing DC extruded cable systems for power transmission at a rated voltage up to and including 800 kV. CIGRE TB 852, 2021

- Lapthorn, Schichler: Medium Voltage DC Cables - A Look to the Future. Jicable, Lyon, France, Report E1-2, 2023

- Rupp, Burt, Schichler, Brüske, Egea-Alvarez, Jambrich: MVDC Grids to Facilitate the Roll Out of Renewables. CIRED, Rome, Italy, Report 1043, 2023

- Ratheiser, Buchner, Schichler: Transmission Capacity of MVDC Cable Systems by Using Extruded MVAC Cables. Conference on High Voltage Engineering, Berlin, Germany, 2020 (in German)

- Ratheiser, Schichler: MVAC XLPE Cables for MVDC - DC Conductivity of Plaque Samples During Temperature Changes. Nord-IS Conference, Trondheim, Norway, 2022

- Buchner, Schichler: Review of CIGRE TB 496 regarding Prequalification Test on Extruded MVDC Cables. Nord-IS Conference, Tampere, Finland, 2019

- Ratheiser, Schichler: Review of IEC 62895 regarding Electrical Type Tests on extruded MVDC Cable Systems. Jicable HVDC, Liege, Belgium, 2021

- Kumara, Hammarstrom, Xu, Pourrahimi, Muller, Serdyuk: DC Electrical Trees in XLPE Induced by Short Circuits. Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena (CEIDP), Vancouver, Canada, 2021

- Liu, Liu, Li, Zheng, Rui: Growth and partial discharge characteristics of electrical tree in XLPE under AC-DC composite voltage. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation, Vol. 24, No. 4, 2017

- Ratheiser, Schichler: Dielectric Strength of XLPE Plate Samples under Transient Overvoltages based on CIGRE TB 852. 14th ICPADM, Phuket, Thailand, 2024