D2 - Quantum Key Distribution for MPLS-TP Traffic Encryption

Authors

Ramon BÄCHLI, Mohammad-Amin SHOAIE, Rouven FLOETER, Vivek PALANGADAN - Hitachi Energy, Switzerland

Axel FOERY - ID Quantique, Switzerland

Summary

The power sector is facing challenges to transmit mission-critical data securely across their wide area networks (WANs) while meeting the stringent performance requirements without any compromise. Due to the criticality of such systems for the operation of the infrastructure, as well as the complexity of migrating systems being permanently used, long living and future proof solutions are of the highest importance. This creates challenges for most existing encryption methods, as traditional cryptographic methods are vulnerable to cryptanalytic attacks from quantum computers, once available. This would compromise the security of critical data and opens the door to attacks on critical infrastructure.

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) promises ultra-secure key disctribution based on the principles of quantum physics by providing forward secrecy and anti-eavesdropping of private key exchange. Consequently, mission-critical system operators such as electrical grid operators are considering the disruptive innovation of QKD channels for secure key distribution as a basis for user data encryption on a highly reliable Multiprotocol Label Switching-Transport Profile (MPLS-TP) network.

This paper presents a solution where for the first time QKD technology is utilized by MPLS-TP encryptors to successfully exchange keys for the use of symmetric encryption. Symmetrical encryption is then used to encrypt the services such as differential protection application. Critical performance metrics of this service such as latency, jitter and wander as well as delay asymmetry are measured and summarized. A verification of the suitability of the solution for such critical applications is done and considerations on availability and resiliency of the solution are included.

The presented solution does not only meet all the requirements in terms of communication channel performance such as latency or channel symmetry, availability or cybersecurity but also allows a gradual implementation and later addition of cybersecurity elements (e.g., a QKD system) once it is deemed as needed.

Keywords

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD), MPLS-TP, ETSI GS QKD 014, Encryption, IEEE 1588 PTPv2, Quantum computing, Post Quantum Cryptography (PQC), Wide Area Network (WAN), Operational Technology (OT), Cybersecurity1. Introduction

Operational Technology (OT) communication networks of transmission and distribution grid operators are migrating to packet switched technologies, in particular MPLS-TP, which provides provenly the best option for technology migration [1]. Along with the technology migration, additional requirements in the area of cybersecurity challenge the implementation of OT networks. OT networks do not only need to comply with the strict performance requirements of the critical applications requiring communication services, be economical in operation and secured against cybersecurity threats, but also fulfil extended life cycle of 15 up to 20 years of operation. This brings new challenges to such networks, especially considering the development around quantum computing and the proof that quantum computers will be able to break conventional encryption, which is based on the difficulty of factoring large numbers. This puts the security of existing encryption systems that are currently deployed at risk.

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) technology can alternately distribute keys without the risk of interception or eavesdropping. The QKD channel employs the quantum mechanics properties of photons to securely distribute encryption keys between end points. Any attempt to intercept or measure the photons will result in a change in their state, alerting the two parties on the presence of an intruder which in turn stops unsecure key exchange.

The ETSI GS QKD 014 standard [2] interface enables the exchange of encryption keys between trusted WAN and QKD appliances. Coupling the QKD key distribution method with the outstanding performance characteristics of MPLS-TP networks that are presently rolled out will enable the development of highly secure, reliable, and performant wide area networks being future proof even in the post quantum computing era.

2. Requirement

2.1. Cybersecurity requirements in OT networks

Securing WAN in OT networks against emerging cybersecurity threats, including quantum computing and its consequences to established cryptographic methods, involves a complex array of technical, legal, and regulatory challenges.

Several technical factors contribute to the vulnerability of WAN in OT networks, each adding to the complexity of maintaining robust security. WANs cover large geographical areas and offer a larger attack surface for hackers, e.g., through unmonitored fiber optic connections which increases the risk of data interception and eavesdropping. Additionally, WANs in OT environments are often comprised of a diverse mix of technologies, including legacy systems. Traditional encryption methods used in WANs may not be sufficiently robust to protect against advanced cyber threats, especially with the advent of quantum computing technologies that have the potential to break many of the current encryption algorithms.

Key threats and attack possibilities

In OT networks, encryption serves as a critical solution to various key threats and attack possibilities. It addresses the risk of data interception and eavesdropping, ensuring that the integrity of all data is protected.

A significant threat in OT environments is unauthorized data modification. Here, encryption, in combination with integrity-checks ensures data remain unaltered during transmission. Encryption also plays a pivotal role in securing remote access, where applied to OT systems, protecting against unauthorized access and data breaches. Furthermore, encryption is key in securing authentication mechanisms, particularly in encrypting login credentials and access-control information, which helps preventing unauthorized access to critical OT systems. For legacy systems in OT, which often lack modern security features, encryption adds a necessary layer of security to protect associated data.

Best security practices assume that an attacker has in-depth knowledge of the encryption algorithm, and that the security of the system depends fundamentally on the security of the underlying encryption key. To provide adequate security, the key must be unique, truly random, and stored, distributed, and managed securely. The best way to generate truly random keys is through Quantum Random Number Generation (QRNG), which provides a provably secure entropy for the generation of encryption keys [3]. However, the problem of secure key distribution can be only solved by QKD thanks to the principles of quantum physics.

Legal compliance and regulatory framework

Alongside general data protection laws, companies operating OT networks are bound by industry-specific regulations. These regulations vary across different regions and sectors, setting forth specific requirements for data security and privacy. Compliance with these standards is not optional; failure to adhere to them can result in severe legal consequences. Given the potential threats posed by quantum computing, it's imperative for these OT networks to be fortified with appropriate security measures.

There are several industry standards and regulations for WAN in OT networks that ensure security and data protection. The following standardisation and regulatory organisations are currently working on quantum-safe communication and are planning on publications in the coming years: NIST, IEC 62443, ISO 27001, NERC CIP.

The integration of advanced cryptographic techniques like Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) and QKD, adherence to industry standards, and the development of a robust cybersecurity culture are crucial components of a comprehensive security strategy.

2.2. Operational requirements

Essential applications for grid operation require high availability since successful and stable grid operation depends on those services. Typical availability requirement is 99.999%, which implies maximum 5min 15s interruption time per year.

Service availability can be highly impacted by potential cyberattacks on the grid’s telecommunication network. The studies conducted by international organization recommends replacing public key cryptography in transmission and distribution utility network [4] [5]. When adopting new encryption methods, it is important to assure low service interruption due to update process and patch management. Therefore, frequent update of cryptographic solutions is not feasible in OT networks. Eventually, the introduction of encryption on transport network shall be resilient against various key distribution failure scenarios and shall not impact service availability.

In order to ensure the service availability requirements, the entire encryption solution (consisitng of key distribution and service encryption solution) has to be designed for high availability not only in case of normal operations but also for potential attack or failure scenarios.

2.3. Life cycle requirements

OT networks are operational all the time (24/7, 365 days a year) since they transmit the data needed for grid operation such as Teleprotection signals, SCADA data and operational voice. This continuous operation, coupled with the strong focus on operational aspects and a moderate inclusion of new applications and devices, leads to a completely different approach of operating the communication infrastructure. OT networks in mission-critical area are operated typically for 10-15 years, sometimes even beyond 15 years. Any solution deployed in such networks needs to comply with those life cycle requirements. Otherwise, this would lead to early replacement of infrastructure, increased failure rate or potentially unsecure solutions. Looking from cybersecurity point of view it is important that the implemented solutions enable meeting the cybersecurity requirements for the entire expected operational period of the OT networks. Failing on this could lead to degraded security levels, severe needs for additional cybersecurity counter measures or early replacement of the OT communication network. Life cycle requirements are applicable to the key distribution system as well as the service encryption solution.

2.4. Time accuracy requirements

Time is a critical asset in modern grid operation and the basis for any digital application. The requirements on time accuracy for power utility applications is well specified as part of IEC 61850-5 and ranked from T1 (1ms) up to T5 (1μs). The 1ms requirement is used for time stamping of fault and event recorder entries. More stringent requirements such as T4 (4μs) or T5 (1μs) is required for time tagging of IEC 61850 sampled values (SV) or Synchrophasor applications [6]. Modern communication systems supporting Precision Time Protocol (PTP IEEE1588v2) or external systems based on GNSS are able to provide this accuracy. Since distribution of accurate time information through WAN using PTP is gaining interest, accuracy as well as availability requirements need to be ensured in the proposed approach. Such time accuracy requirements are applicable to the services using the encrypted link.

In particular, when PTP is distributed through multiple nodes, each transient node acts as a Telecom Transparent Clock (T-TC) and adds the residence time to the PTP correction field. Transient nodes may also generate timing noise that accumulates across multiple sections and negatively impacts the time accuracy. Therefore, requirements of T-TCs become critical. Table i summarizes noise generation requirements of T-TC Class-A and Class-B while Class-C requirements are still for future study. In Table i, Time Error (TE) measures the phase shift while Mean Time Interval Error (MTIE) and Time Deviation (TDEV) characterize the phase stability of the clock when passing through the T-TC.

| Parameter | Condition | Class-A | Class-B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max |TE| | Unfiltered, 1000s | 100ns | 70ns |

| cTE | Average over 1000s | 50ns | 20ns |

| MTIE | 0.1Hz low-pass filter, Const. Temp, 1000s | 40ns | 40ns |

| TDEV | 0.1Hz low-pass filter, Const. Temp, 1000s | 4ns | 4ns |

2.5. Application performance requirements

Requirements of Teleprotection (distance and differential protection application)

The most critical application for reliable grid operation is the protection of the High Voltage (HV) powerlines, Transformers and other primary equipment. The requirements of protection applications are summarized in this section. They need to be ensured by the encyrpted service provided by the wide area network and are the benchmark to evaluate the suitability of the proposed approach.

The fault clearance time (Tc) is a critical performance parameter of any protection system and is defined in the IEC 60834-1 standard. A typical value for a HV transmission line is 3-6 power frequency cycles. Tc is broken down in requirements for all the different subsystems. For Teleprotection systems, the maximum transmission time (Tac) is the critical performance criterion when it comes to latency. For digital communication systems, Tac should be < 10ms, which is recommended for all kind of line protection schemes of HV lines, independent of the type of communication interface [7] [8]. Other organizations issue recommendations for Teleprotection communication channel latency, which go even beyond the requirements defined by IEC. For example, CIGRE recommends having a maximum latency time of 5ms [9].

Differential protection

Differential protection relies on the comparison of simultaneous (synchronized) samples of currents from the line ends and demands very stringent requirements on signal transfer delay, delay variation and delay symmetry. Channel latency needs to be compensated to enable comparison of samples.

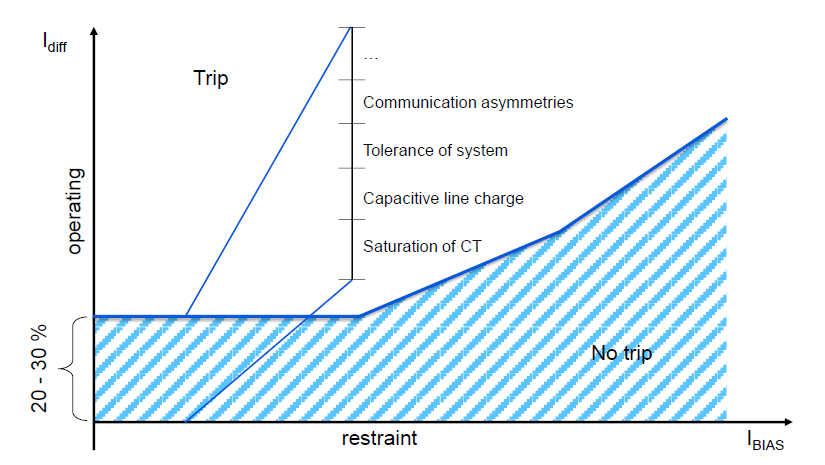

This typically happens through relays measuring the latency of the communication channel using echo timing (round-trip method, means measuring the round-trip delay and divide it by 2). Any time deviation from the calculated channel latency imitates a virtual fault current, which could lead to unwanted tripping of circuit breakers if the tolerance threshold is reached (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Tripping characteristics of differential protection relay

Accordingly, channel delay asymmetry and delay variation are key performance parameters for differential protection. CIGRE Technical Brochure 192 “Protection using Telecommunications” [7] requests, that a high performing line carrying differential protection provides a maximum delay asymmetry and delay time variance of < 0.1ms, though more recent publications accept values of < 0.2ms considering that lower values are very difficult to achieve with communication circuits other than direct fibres [9].

Distance protection

Distance protection is based on the transfer of binary commands. In comparison to differential protection no direct comparison of current values happens on both sides. This relaxes the requirements in terms of symmetrical delay and jitter & wander free communication channels. Since major implication on securing the OT network by applying PQC methods is expected around availability, latency as well as jitter and wander, all measurements are done against differential protection requirements. Distance protection specific performance parameters such as probability of missing a command as defined in IEC 60834-1 need to be ensured by the specific application implementation.

3. Quantum Key Distribution technology

3.1. Quantum computing and cryptographic vulnerabilities

Quantum computers leverage quantum bits (qubits) to perform calculations. Unlike classical bits, qubits can exist in multiple states simultaneously (superposition), enabling quantum computers to solve certain problems much faster than classical computers. Quantum algorithms like Shor's algorithm can factorize large numbers efficiently, threatening RSA and ECC encryption, which rely on the difficulty of factoring as a security premise.

In addition to the risk posed to asymmetric encryption methods such as RSA and ECC, quantum computers also present a significant threat to symmetric encryption, albeit in a different way. Symmetric encryption, which uses the same key for both encryption and decryption, is vulnerable to Grover's algorithm in the realm of quantum computing. Grover's algorithm provides a quadratic speedup for searching unsorted databases and is applicable to finding encryption keys [10]. For example, a 256-bit key, considered secure against classical attacks, would have the same level of security as a 128-bit key against a quantum attack, as 256/2 = 128.

This reduction in complexity, while less dramatic than the impact of Shor's algorithm on asymmetric cryptography, still poses a significant threat to current symmetric encryption standards. It implies that symmetric keys would need to be doubled in length to maintain the same level of security against quantum attacks. Therefore, in a post-quantum world, a symmetric key that would typically be 128 bits long for security against classical computing attacks would need to be increased to 256 bits to achieve equivalent security against quantum computing attacks. The implication of this is significant for current encryption practices. Doubling the key length can increase computational and resource requirements, potentially impacting performance in systems that rely on symmetric encryption for security.

3.2. Quantum Key Distribution (QKD)

QKD technology solves the problem of key distribution by allowing the exchange of the encryption key between two remote parties with absolute security guaranteed by the fundamental laws of physics. This key can then be used securely with conventional encryption algorithms. In QKD technology one encodes the value of a digital bit on a single quantum object. According to quantum physics, the mere fact of observing a quantum object perturbs it in an irreparable way. As a result, any interception of digital bits will necessarily translate into a perturbation because the eavesdropper is forced to observe it. This perturbation causes errors in the sequence of bits exchanged by the sender and recipient. By checking for the presence of such errors, the two parties can verify if an eavesdropper was able to gain information on their key. It is important to stress that since this verification takes place after the exchange of bits, one finds out a posteriori whether the communication was intercepted or not. This is why the QKD technology is used to exchange the key and not the information. Once the key exchange is validated, and the key is provably secure, it can be used to encrypt data.

To transform a current network into a quantum-safe network, QKD appliances shall be installed in various sites where key consumers are located. In addition, a dedicated Quantum Key Management System (Q-KMS) is required for key management. Q-KMS is a networking framework to route symmetric encryption keys between users, as opposed to conventional KMS that is more a centralized solution. In the simplest case, two QKD appliances are connected point-to-point through an optical fiber and continuously distribute keys, which they store at each end-point until it is requested by the encryptors at either end-points.

Such a point-to-point solution works up to 24 to 30dB optical attenuation in the fiber, which corresponds to a range of about 120km, depending on the quality of the optical network. However, the range can be extended to longer distances, using so-called Trusted Nodes. These trusted nodes that are managed by Q-KMS perform key hopping, whereby keys are generated at a starting node and transferred securely from node to node until the end node. Using a similar technology, it is possible to build various types of QKD networks, such as ring networks and star networks. The test setup in this paper considers a point-to-point solution. However, results presented in section 5 can be also generalized to other QKD networks.

4. Test setup

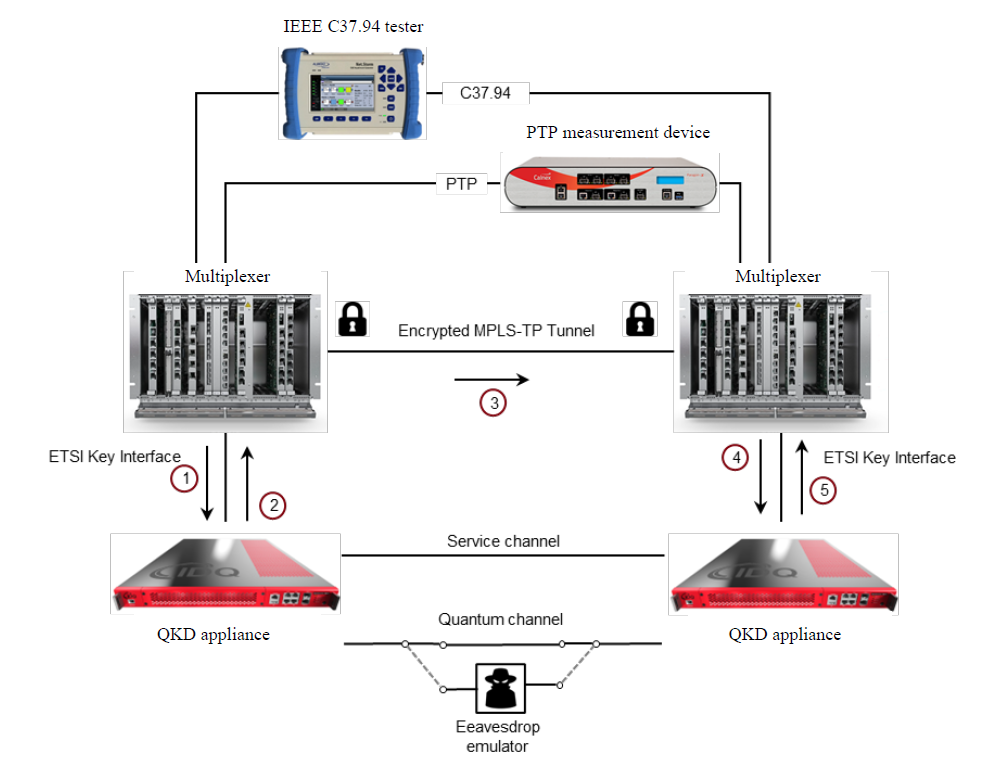

We demonstrated the integration of QKD technology and MPLS-TP encryption in two different setups i.e., lab and field setup. The key update resiliency requirement from section 2.2 is verified in both lab and field setup. The time accuracy and application performance require-ment from sections 2.4 and 2.5 are verified in the lab setup. Mea-surement results are presented and discussed in section 5. Figure 2 shows the lab setup used for integration of the QKD appliance with the multiplexer using the ETSI GS QKD 014 key interface.

Two multiplexers with wire speed encryption cards are connected over 10G optical interface. An encrypted MPLS-TP tunnel is created between two multiplexers. The tunnel transports services that are used for time-error and delay measurements. The quantum channel and service channel of QKD appliance (Alice on the left and Bob on the right) are interconnected via two optical fibers. As mentioned in section 3, Alice and Bob use the quantum channel for generating the secured encryption keys. The service channel is used to exchange additional information such as post-processed data. The eavesdrop emulator is a passive component that can be inserted in the quantum channel using fiber cables. This component emulates interception of the photons that are used during key generation process between Alice and Bob.

A circuit emulation service is configured between the nodes over the IEEE C37.94 interface which is a Teleprotection specific card. The circuit emulation implementation on the IEEE C37.94 interface can guarantee a deterministic end-to-end delay on both forward and return path. This implementation minimizes the delay asymmetry [11]. The C37.94 test stream is used to inject data and measure the performance of the communication channel. This stream is transported over MPLS-TP WAN port and encrypted.

The encryption unit performs symmetric encryption utilizing AES-256 algorithm using a session-key to encrypt and decrypt data. The session-key is generated per direction using a master-key in combination of a seed from the on-board QRNG chip. The master-key is identical on both sides and is obtained from the QKD appliance. Session-key and master-key are periodically updated to increase the safeguarding factor. Session-key is typically updated every few minutes up to few hours while the master-key is normally updated every several hours up to several days.

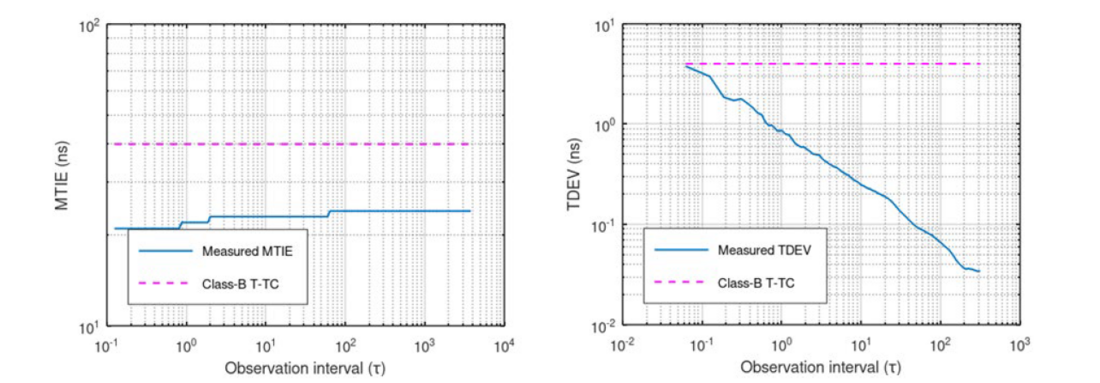

The C37.94 tester measures one-way delay and delay asymmetry for C37.94 test stream over the encrypted MPLS-TP link. The PTP measurement device measures time-error of PTP packets and extracts statistical parameters such as MTIE and TDEV for PTP packets that traverse the encrypted MPLS-TP link. In this setup both multiplexers are configured as transparent clocks. Measured MTIE and TDEV are shown in Figure 3.

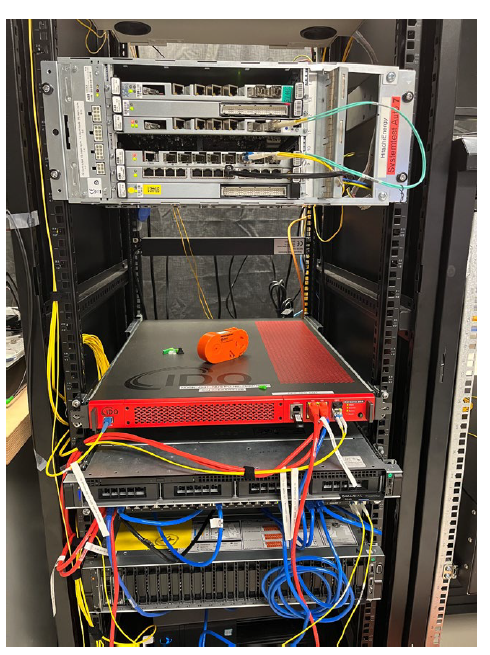

As shown in Picture 1, the integration of QKD with MPLS-TP encryption card was also tested in National Quantum-safe Network (NQSN) infrastructure in Singapore. In collaboration with universities, vendors and governmental agencies, NQSN provides a testbed to demonstrate the technical feasibility of Quantum-safe technologies aiming to deploy commercial technologies for future use [12].

The NQSN setup is similar to lab setup except that multiplexers and QKD appliances are located at NUS (Centre for Quantum Technologies) and NTU (Fraunhofer Singapore Research) universites connected via 32.48km fiber link. The ETSI GS QKD 014 interface on encryption card and QKD appliance are connected using an Ethernet switch. The Ethernet switch allows for adding more key consumers in the future by adding logical interfaces on QKD key interface. A video stream was transmitted over an encrypted tunnel between two sites to verify traffic continuity.

Picture 1 - Field test setup at NQSN for integration of QKD system with MPLS-TP encryption

5. Results

In this section we discuss results from different measurements used for verifying the requirements. Section 5.1 verifies the resiliency of updating master-key on the multiplexer’s encryption card using the results acquired from the lab and NQSN setup. In section 5.2 we discuss delay measurement on C37.94 stream over the encrypted link while section 5.3 presents time-error analysis of PTP packets over the encrypted link. Both section 5.2 and 5.3 results are acquired from the lab setup.

5.1. Master key update resiliency

To verify the resiliency of master-key update on the multiplexer, we first revisit the update sequence during normal operation. Figure 2 encircles various steps during a master-key update process where the encryption card connected to Alice initiates the process. In fact, these steps describe QKD ETSI GS QKD 014 standard which is independent from QKD or encryptor vendor.

- Step 1: The encryption card connected to Alice sends a request to Alice to get a new master-key.

- Step 2: Upon the request in step 1, Alice provides the master-key to the encryption card as well as the key-ID that is associated to the master-key.

- Step 3: The encryption card from step 1 holds the master-key and sends the associated key-ID to the encryption card connected to Bob via the MPLS-TP link between the two multiplexers.

- Step 4: The encryption card connected to Bob sends a master-key request to Bob while passing the key-ID that was received from the other encryption card.

- Step 5: Upon the request in step 4, Bob provides the master-key to the connected encryption card. This is the same master-key that was delivered to the peer encryption card in step 2.

Initiating the master-key update from the encryption card that is connected to Bob follows the same steps but in the reverse direction.

As mentioned in section 3, QKD appliances continuously generate secured encryption keys and store them on their internal key buffer. In case QKD appliance detects eavesdropping during the key generation process, the affected keys are not stored in the buffer. Therefore, it can be safely assumed that keys that are provided to the multiplexer in steps 2 and 5 are secured.

ETSI GS QKD 014 standard only covers the key delivery process from QKD appliance to encryption devices as explained in steps 1 to 5. However, the implementation of key consumption is vendor specific. The key consumption in the multiplexer is implemented in a way that data transmission is not disrupted during master-key update. This means updating the master-key is a hitless action from encrypted traffic perspective.

To verify the resiliency of master-key update, the two following scenarios were considered. In the first scenario we emulated eavesdropping situation in the lab setup by inserting the passive component in the quantum channel as shown in Figure 2. Immediately after introducing the eavesdrop, the QKD appliances stopped generating new encryption keys. In this situation we triggered master-key update on one encryption card. Depending on the key-buffer condition, the result is described below:

- If the QKD key buffer is non-empty, the master-key is successfully updated on both encryption cards without any traffic disruption.

- If the QKD key buffer is empty and the eavesdropping condition persists, QKD does not return any key in step 2 and hence both encryption cards continue sending encrypted data using the former master-key that was already secure. In fact, the implementation of key consumption on node does not stop the transmission of encrypted data which is essential in mission-critical networks. However, the operator can be notified about the failure of the master-key update. Obviously, the empty key buffer and persisting eavesdropping condition will also generate an alert from QKD appliance.

In the second scenario we emulated QKD link failure in NQSN setup by cutting the link between the multiplexer and the Ethernet switch at Bob’s side. We then triggered master-key update on the encryption card connected to Alice. The result is that master-key is not updated on either side since step 4 is blocked after the link cut. Similar to the first scenario, the node continues transmitting encrypted data using the former master-key which is secure.

5.2. Delay and delay asymmetry measurement

To verify the impact of encrypted MPLS-TP link on the time-sensitive applications, we measured delay and delay asymmetry using xGenius as described in section 4. For the circuit emulated service over the IEEE C37.94 interface, we configured 6ms end-to-end delay on each path. This means the one-way delay is guaranteed to be 6ms, including the forwarding delay from the encrypted MPLS-TP link. Table ii shows the measured delay on the forward and return paths for the C37.94 stream as well as the respective asymmetry. The measured delay on both paths is close to the theoretical value. The error which is about 50μs mainly comes from circuit emulation quantization errors.

| Types of tests (C37.94) | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Forward path delay (ms) | 6.052 | 6.052 |

| Return path delay (ms) | 6.051 | 6.051 |

| Asymmetry (µs) | 1 | 1 |

Since the IEEE C37.94 interface provides a deterministic end-to-end delay on forward and return paths, the asymmetry between the two paths is as low as 1μs. Hence, Table ii proves that MPLS-TP encryption has a negligible impact on the application performance and Teleprotection services over single MPLS-TP encrypted link as required in section 2.5. This conclusion can be generalized to multiple encrypted links since unlike generic circuit emulation service, delay and delay asymmetry over the IEEE C37.94 interface is not impacted by packet delay variations from MPLS-TP network [11].

5.3. Time-Error analysis

Since the Teleprotection service uses time information from PTP, any time inaccuracy will translate into jitter or wander of such time-sensitive application. To verify the impact of encrypted MPLS-TP link on time accuracy, we used a PTP measurement device in the lab setup as described in section 4. Figure 3 depicts MTIE and TDEV graphs as a function of observation interval, τ. We used G.8273.3 Class-B Telecom Transparent Clock (T-TC) mask as for the comparison.

It can be verified that measured MTIE and TDEV of PTP packets over the encrypted MPLS-TP link is well below the mask, thanks to the transparent clock functionality of the multiplexer.

Figure 3 - Measured MTIE (left) and TDEV (right) using Paragon-X over the encrypted MPLS-TP link in the lab setup. Telecom Transparent Clock Class-B mask is added for the accuracy comparison

To estimate the time-error over N encrypted sections, we measured constant time-error (cTE) and dynamic time-error (dTE) on the single encrypted MPLS-TP link and used following formula to calculate the upper bound of error for N sections [13]:

(1) Upper bound error calculation formula [13]

where cTE1, dLTE1 and dHTE1 are respectively constant time-error, dynamic time-error (low frequency component) and dynamic time-error (high frequency component) of single section. The formula discards the time error component originating from the link asymmetry and can be typically neglected if fibers are symmetrical.

Table III denotes the measured values of cTE1, dLTE1 and dHTE1 of the single encrypted section as well as the upper bound values estimated over N=50 encrypted sections denoted as cTE50, dTE50. The estimated values show that even after 50 encrypted MPLS-TP sections the constant and dynamic time errors respectively stay below 300ns and 25ns which fulfills the tightest requirements (1μs) discussed in 2.4.

| Constant Time Error | Dynamic Time Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured values single encrypted section | cTE1 = 6ns | dLTE1 = 6ns | dHTE1 = 24 ns |

| Estimated values over 50 encrypted sections | cTE50 < 300ns | dTE50 < 25ns | |

6. Conclusion

Quantum computing is a potential threat for secure communication services depending on today’s available encryption technology. Especially key distribution using asymmetric encryption methods are at risk. Considering the importance of the critical infrastructure such as electric transmission and distribution systems it is natural that operators of such infrastructure are investing in solutions enabling a secure operation in the post quantum computing era.

The integration of advanced cryptographic techniques such as PQC offer algorithms that are resistant to quantum computing attacks, while QKD provides a method to distribute keys that is theoretically immune to any form of eavesdropping, even by quantum computers.

Protecting wide area operational networks from cybersecurity threats, including quantum computing, requires a multi-layered approach that combines advanced cryptographic technologies, adherence to regulatory standards, continuous monitoring and proactive defense strategies and a strong organizational focus on cybersecurity awareness and training. As the technological landscape evolves, so must the strategies to protect critical infrastructures, requiring ongoing vigilance, innovation, and investment in cybersecurity infrastructure.

The tests performed and described in this paper show that mission-critical OT networks based on MPLS-TP can be fortified with key distribution methods using QKD technology. The presented solution, with technology leading functionality in terms of application centric solutions and the extraordinary robust implementation with local session-key generation being based on real randomness, does meet all key aspects, the performance needed by the applications and the availability needed for reliable grid operation as described in section 2 as well as the cybersecurity needs applicable for critical infrastructure today and in future. Even if an operator does not implement such advanced cybersecurity functionality for the time being, the flexible and modular nature of the used equipment allows an implementation at a later stage, without replacement of hardware or extensive reconfiguration of already provisioned services.

Acknowledgement

The author wish to thank Dr. Jing Yan HAW, Dr. Hao QIN, Dr. Sanat SARDA, Dr. Xiao DUAN & Matthew WEE from NQSN for their technical support in the field test reffered in section 4.

References

- CIGRE, International council on Large Electric Systems Study Committee D2: Information Systems and Telecommunication, Utility Communication Networks and Services, Paris: Springer, 2017. Green Book

- "ETSI GS QKD 014 V1.1.1," 02 2019. [Online].

- "Quantum versus Classical Random Number Generators," [Online].

- MICHAEL J. D. VERMEER, EDWARD PARKER, AJAY K. KOCHHAR, "Preparing for Post-Quantum Critical Infrastructure," 18 08 2022. [Online].

- "Migrating to Post-Quantum Cryptography," [Online].

- IEC, "IEC 61850: Communication networks and systems for power utility automation," IEC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- "CIGRE Technical Brochure 192 “Protection using Telecommunications”," August 2001.

- IEC, "IEC 60834-1: Teleprotection equipment of power systems - Perfromance testing," IEC, Geneva, Switzerland, October 1999.

- "CIGRE Technical Brochure 521 “Line and System Protection using digital circuit and packet com-munication”," CIGRE, December 2012.

- "Grover's algorithm," [Online].

- Bächli, Ramon, Martin Häusler, and Mathias Kranich, "Teleprotection solutions with guaranteed performance using packet switched wide area communication networks," in 70th Annual Conference for Protective Relay Engineers (CPRE), 2017.

- "National Quantum-Safe Network (NQSN)," [Online].

- "Time and phase synchronization aspects of telecommunication networks," 11 2018. [Online].